Reorientations and Paradigm Shifts in Design Praxis and Theory, Design Thinking and Doing

Berlin, 20.01.2025

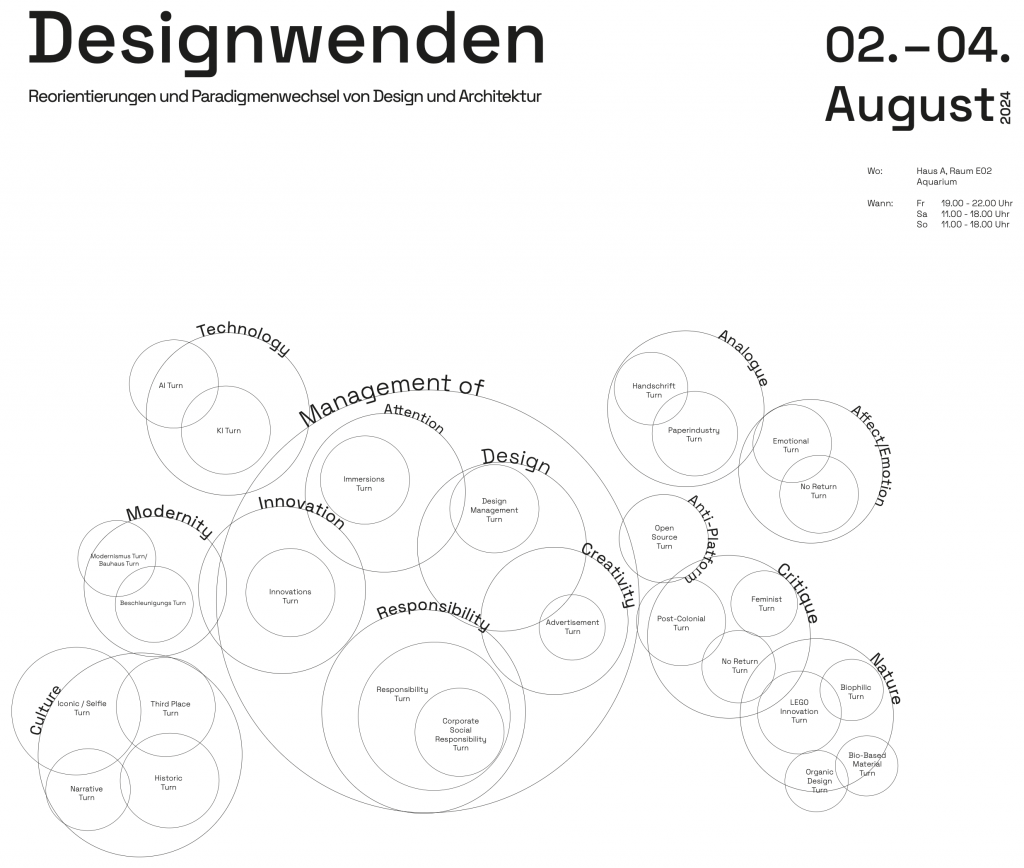

To engage with the histories, present, and futures of design is always also to attend to design turns: major and minor breaks, shifts, reorientations, threshold moments, and paradigm changes through which it becomes clear how design thinks, what it is, what it can do, and what it ought to be. “Design,” in this sense, has never been a stable core so much as a continuous negotiation of guiding ideas, styles, concepts, methods, and responsibilities.

Even the emergence of modern design can be described as a turn. Modern design arises as the product of a far-reaching social, cultural, and economic transformation: the Industrial Revolution of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Mass production and machines supplemented or replaced artisanal making; standardization, functionalization, typification, and the division of labor generated new demands for conception and production—and continue to shape design’s self-understanding today. At the same time, the industrial turn in the applied arts and crafts reliably produced a counter-turn: the Arts and Crafts movement responded by reasserting the value of craftsmanship and traditional methods. Yet even then there was no simple “return.” Counter-turns, too, operate under altered conditions and generate new hybrid forms.

At the beginning of the twentieth century, another reorientation follows: De Stijl and the Bauhaus—despite their internal conflicts and heterogeneity—condense a functionalist impulse that combines formal discipline, minimalism, technological orientation, and promises of social reform. Such “schools” are not to be understood as homogeneous blocks, but rather as contested arenas of programmatic decisions. Later, postmodern turns react to the strictness and universalism of modernism by strengthening plurality, signification, irony, and at times dysfunction and play. These vectors do not unfold linearly, but in parallel, intersecting and overlapping into the present.

Design turns, however, are not only shifts in ideas; they are often also methodological and epistemic. New procedures and modes of organization—from industrial production techniques to cultural techniques of labor organization—change what counts as “good” design and how design is justified. A prominent example is the paradigm of user-centered design, which systematically places users and affected persons at the center—an overdue correction to purely object- or technology-driven logics. At the same time, we can observe a further recent re-centering: in the context of ecological crises, diagnoses of exhaustion, and posthuman debates, reference points shift toward life-centered, nature-centered, or holistic design, with the aim of taking more-than-human relations, dependencies, and consequences seriously. This turn, too, will produce adjacent and counter-turns: every centering generates blind spots and conflicts over priorities.

On the praxeological and media level, design turns often appear as tool turns. The revolutions of the computer and digital age since the 1970s and 1980s have not only transformed products; they have also transformed modes of designing and making: digital image processing, CAD, simulation, 3D modeling, and digital fabrication have shifted standards of variation, speed, precision, and scalability. Every change in the dominant tool paradigm is therefore also a change in design thinking—tools co-structure perception, options, and decisions. In the current, much-discussed AI turn, this dynamic intensifies once more: generative systems and automated modeling redistribute authorship, division of labor, criteria of quality, and attributions of responsibility, without the outcomes of this transformation yet being clear. We are in the midst of an ongoing turn—and that is precisely what produces its orientation problem.

How, then, can we act within this dynamic? Design must—precisely because its stances, methods, and tools are not finally settled—recalibrate again and again. Flexibility here is not arbitrariness, but a competence: the ability to redefine aims, means, and consequences under changing conditions. At the same time, design is marked by a constitutive relation to the world: it does not stop at description or critique, but intervenes—by shaping objects, systems, spaces, interfaces, and infrastructures. In this way, the discipline itself becomes an agent of change. Products and artifacts of design enable (and often compel) shifts in perspective in use; they establish new practices and reorganize sociocultural routines.

From this efficacy follows responsibility. Design should remain a mobile, multiply conditioned practice and must not uncritically follow industrial, political, or cultural path dependencies. Before any act of design there is an orientation of attention: toward central and peripheral things, toward strong and weak signals, toward dominant and marginalized persons and groups—and equally toward more-than-human participants such as animals, plants, environments, and technical things. Crucial here is the possibility of a U-turn: the capacity for a justified reversal, especially under conditions of increasingly rigid technological, ideological, and platform-capitalist dependencies. This requires a reflexive design competence: the ability to adopt a second-order observational position that can gain critical distance without losing proximity to the field; that remains dialogical and, within design’s “in-between”—between analysis and intervention—can make decisions responsibly. And when necessary: to design the next reversal.

At the Faculty of Design at the HAWK in Hildesheim, we engage as a collegium in dialog with these changing conditions and the design turns associated with them, in order to enable our students to develop a sharpened gaze and a reflective capacity for action—so they can participate in shaping future design turns.

Text: Konstantin Haensch

English translation of the published text:

„‚Designwenden‘ – Reorientierungen und Paradigmenwechsel der Gestaltung /‘Design Turns’ – Reorientations and Paradigm Shifts in Design“ in „Design aus Hildesheim“ (2025)